Floyd had been working on “Sand Cave” for nearly three weeks, digging through loose rocks and debris to reach limestone underneath. Four days before his last descent into the passageway, he had set off some dynamite to clear some of the rubble. He had taken off his wool coat and left it at the top, making it easier for him to squeeze through incredibly tight passageways.

Working through a new passageway cleared by the dynamite, Floyd reached a pit before his lantern began to flicker. Knowing he could explore further later, he started to work back up. In the crevice, he pushed his lantern ahead of him and it fell over and went out. In full darkness, he turned on to his back and inched through by wiggling his hips and digging his feet into the sides. He unlodged a rock that landed on his left ankle, pinning him in the passageway with this arms trapped at his sides. Clawing at the gravel around him only packed him in deeper and water began to trickle on to his face.

As rescuers soon realized, the conditions of the cave were not ideal. At the surface, Kentucky temperatures in the dead of winter reached freezing, especially at night. Underground temperatures hovered constantly around 54 degrees. However, due to the stormy weather and the permeable ground, water filled the cave. “A normal sized man immersed in fifty-four degree water will die of hypothermia in a little over four hours.”

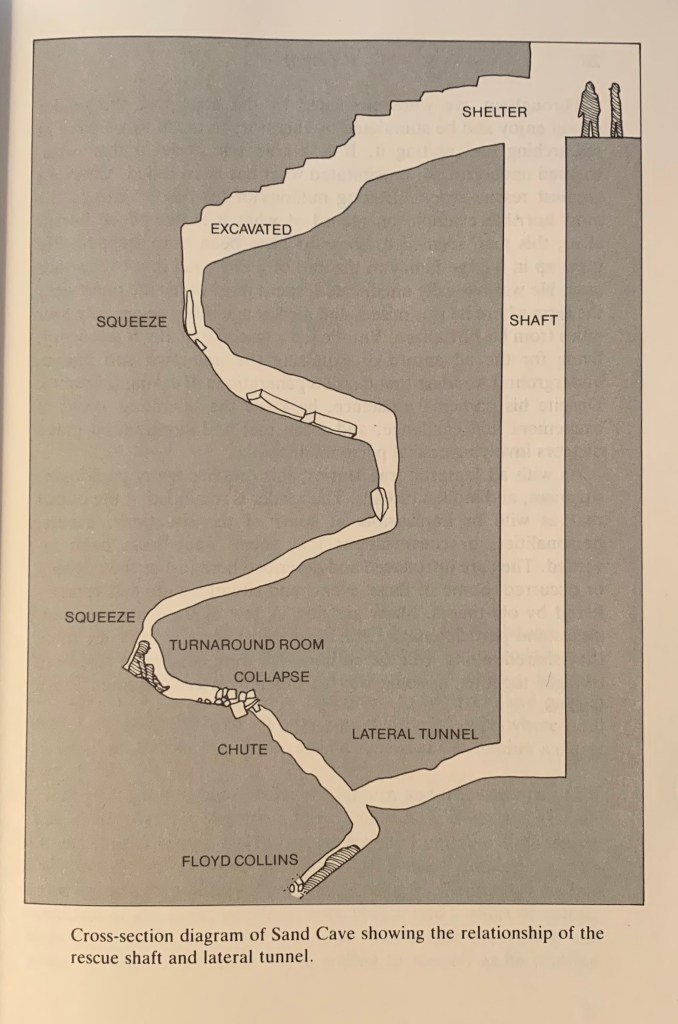

The water also made the cave slick and muddy, freezing rescuers who had to crawl to avoid jagged rocks and forge through tight passages. And even when they reached Floyd – many men claimed to and didn’t actually – it was nearly impossible to make any progress. Moving into the space head first meant you couldn’t support yourself, but going feet first meant you’d have to crouch and use your arms. There was so little room, you couldn’t get your arms over the top of the man, let alone many tools that could assist. Every man that emerged from the cave did so exhausted, on the verge of collapse.

“Those who had never experienced the feeling of being in a contorted position in a tiny earthen space easily misunderstood Sand Cave’s particular rescue problems: the icy water, the mud, the tight squeezes, the twists and turns, the collapsing walls, the protruding rocks, the shifting gravel, the soggy clothes, the clammy numbness, the formidable barrier of the massive limestone block above the victim’s head, and the inaccessibility of the small rock that held his foot,” (111).

For Floyd, being trapped in such extreme conditions led to various mental states. When he was initial trapped, he screamed until is voice was gone and suffered through the pain in his hands and feet, all while losing heat and surviving without food or water. After being found and having some of his basic needs fulfilled, Floyd was calm, almost patient, while rescue efforts began. Here, he experienced the first bought of hallucinations – dreaming of angels, food, and his brother Homer. While Miller first entered the cave, Floyd was in control of all of his faculties, and almost witty. The failed harness rescue left him shaken, hysterical, and in more pain. His extremities started to numb. From here, Floyd became doubtful, upset, and incredibly frightened, finding moments of calm talking with Homer and Miller. When rescue efforts got tougher and tougher, Floyd transitioned from hopeful and encouraging to paranoid and scared, slipping in-and-out of conscious states, sobbing in terror, not wanting to be left alone. After the collapse, he started lying that he had freed himself, hoping that his rescuers wouldn’t give up.